If I was back in Manhattan I would hike up to the New-York Historical Society for a look, if they allow it, at the John Pintard Papers, specifically the undated "Handwritten Notes" there. I want to learn more about the context and meaning of this odd quotation by Charles W. Jones from the "private notebook" of John Pintard:

"I told [Moore] not to speak slightly or disrespectfully of what he was totally ignorant. Is he a sample of the professors of the local school— . . . Eheu! professor."Professor Jones's point is easy to get: Moore could be stuffy. While honoring Clement C. Moore as "a most admirable man," the distinguished medievalist wants us to know that Moore was also pedantic and occasionally annoying in the way that academic types tend to be. Fair enough. Unfortunately, however, Professor Jones did not footnote his quotation beyond the citation of Pintard's "private notebook." And as a clinching illustration of Moore's supposedly irritating manner, the quote sounds better than it really is. First of all, what did Moore say to Pintard that so offended him? Second, I don't like the editorial brackets around Moore's name, and I hate the ellipses between the dash after Pintard's "school" and Pintard's exclamation, "Eheu!" In such a short quotation, brackets and ellipses combined are a bad sign, perhaps more indicative of the quoter's need to press than anything else. What's missing?

I'd like to know where and how Moore's name first appears in the "private notebook," before the bracketed part. Jones does give a bit of the broader context for Pintard's complaint, which is that John Pintard and Clement C. Moore

"were working together with Bishop Hobart and others for the establishment of the General Theological Seminary."That by itself puts the date of Pintard's diary entry around 1821. Jones to his credit read all of Moore's published Poems, but in 1954 he did not have the benefit of Samuel W. Patterson's biography The Poet of Christmas Eve, or Powel M. Dawley's The Story of the General Theological Seminary. Jones does not mention Moore's hugely important grant of land for the future seminary. Also Jones seems not to perceive or care about the significance of Pintard's term "local school" which considerably narrows the window for dating Pintard's diary comment. Indeed, at this time Pintard was actively working against John Henry Hobart, not with him. Bishop Hobart then supported the seminary as a "local school" controlled by the diocese of New York, whereas Pintard strongly advocated for a truly "general" institution of the Protestant Episcopal Church as a whole. Accepting the authority of Bishop Hobart, Moore served on the small faculty during the brief period of the New York seminary's existence as a "local school." When the General Theological Seminary returned from New Haven and merged with the New York school in 1822, Moore stayed on with a new job title, revised from "Professor of Biblical Learning" to "Professor of Oriental and Greek Literature." Even in Hobart's diocesan school, Moore stuck to his area of expertise. He and his students read Genesis in Hebrew:

With the Professor of Biblical Learning, the students, on the opening of the seminary, entered immediately upon the study of the Hebrew language; and, on the 1st of August, when the session ended, they had read, in that language, the first eighteen chapters of Genesis. In the course of this reading, their attention has been directed to such annotations of Patrick and Lowth, and other commentators, as appeared most interesting and important. --Report of the professors of the Theological Seminary, dated October 9, 1821 and reprinted in The Christian Journal, and Literary Register on April 1, 1822.The real firecracker in this 1821 scenario is Pintard. As Herman Melville's friend John W. Francis said,

John Pintard was a man of extensive historical, geographical, and above all, didactic information. I hardly speak within the charge of exaggeration, when I affirm that he knew nearly all Dr. Johnson's writings by heart. You could scarcely approach him without having something of Dr. Johnson's thrust on you. He was versed in theological and polemical divinity—Stillingfleet was his idol; of South he was a great admirer, and in the progress of Church affairs among us, he was ever a devoted disciple.Whatever Pintard might have written negatively and privately about Moore in 1821, he had far worse things to say back then about Hobart. So the clinching "Eheu! professor" quote really is more revealing of Pintard than Moore. Considering Moore's recent generous gift of land in February 1819, and considering their prior involvement as fellow Trustees of the New-York Society Library, Pintard's tone seems ill-matched to Clement C. Moore. Could Pintard have had in mind a different Moore? Or maybe Pintard's displeasure was directed at a different professor in the "local school," perhaps Gulian C. Verplanck, or Benjamin T. Onderdonk. Pawley says flat out that Pintard "did not like" Onderdonk, quoting Pintard's view of Onderdonk as Bishop:

--Semi-centennial Celebration

The Bishop of this diocese is perhaps as a Divine, below mediocrity. His excellence consisted in being the satellite of Bp. Hobart, whose bigotry he follows without his talents happily for us. --Letters from John Pintard to His DaughterIt's an interesting case study in the interpretation of documentary evidence. Don Foster in Author Unknown seizes on the negative image of Moore, of course, which he exaggerates by stating that Moore was "fond" of talking in the insulting way that Pintard appears to describe in his "diary" as partially quoted by Charles W. Jones. Trying to paraphrase Jones on the Knickerbocker Santa Claus, Foster imagines that

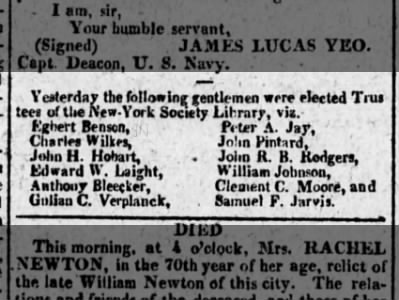

"The New York philanthropist John Pintard first met Clement Moore in 1821 while working to establish the General Theological Seminary." --Author UnknownBut Jones did not say (and probably did not know) when they first met. 1821 seems way too late, when Moore was 42 years old and Pintard 62. On January 14, 1805 Clement C. Moore's father Benjamin Moore was named First Vice President of the New-York Historical Society, which Pintard and others had only just founded the previous November. Eight years later, Pintard and Clement C. Moore (and Gulian C. Verplanck) were named together as Trustees of the New York Society Library, "ELECTED IN APRIL, 1812." According to the list of Trustees Past and Present on The New York Society Library website, Pintard became a Trustee of the Library in 1790; Moore in 1811.

On April 25, 1815 John Pintard and Clement C. Moore again were named Trustees of the

New-York Society Library, along with John H. Hobart, Gulian C. Verplanck, and Samuel F. Jarvis. All five played major roles also in the establishment of the General

Theological Seminary.

On the other hand....Foster's idea that Pintard and Moore "first met" in 1821 is one way of trying to account for the genuine strangeness of Pintard's negative view of Moore, as quoted with brackets and ellipses by Charles W. Jones. After attending the funeral of Moore's wife in 1830, Pintard told his daughter that he and Moore "have been always on the most friendly terms" (Letters from John Pintard to His Daughter Volume 3). Having more context would enable us to understand better what Pintard wrote in 1821, exactly, and what he meant.

Apart from the questionable quotation that Charles W. Jones introduced from Pintard's "private notebook" in 1954, Clement C. Moore's contemporaries regarded him as not only admirable, but likeable. For example, this 1824 overview for the Gospel Messenger and Southern Christian Register (signed "A.") of the new General Theological Seminary praises Moore for his scholarship and "agreeable manners":

Mr. Clement Moore, son of the late Bishop of New-York, fills the professorship of “Oriental and Greek Literature.”

It is well known that this gentleman is an accomplished scholar, and that he has for more than twenty years been a devoted student of the Hebrew. He is the author of a very useful Hebrew Grammar and Lexicon; and it is no small occasion of satisfaction, that his services in this department have been secured to our Seminary. Mr. Moore had previously given a pledge of his interest in this institution, by the generous donation of sixty lots at Greenwich, near the city of New-York, which at some future period must be immensely valuable. It needs scarcely be added, that his character, learning, and agreeable manners cannot fail to attract towards him the highest respect and regard from his pupils. --Gospel Messenger and Southern Christian Register - January 1, 1824

I don't know anything about Moore other than what you've been posting, but this appears to be the standard Moore family genealogy, with a lengthy entry on Clement beginning on p. 104:

ReplyDeletehttps://archive.org/stream/revjohnmooreofne00moor#page/104/mode/1up

I did not have this, thanks Bob.

ReplyDeleteOff topic: Several Melville items in the latest Notes & Queries, also:

ReplyDeletehttps://academic.oup.com/nq/issue/64/1

Good, almost forgot I have a current subscription. Exeter Riddles! How I miss Jim Anderson.

Delete