|

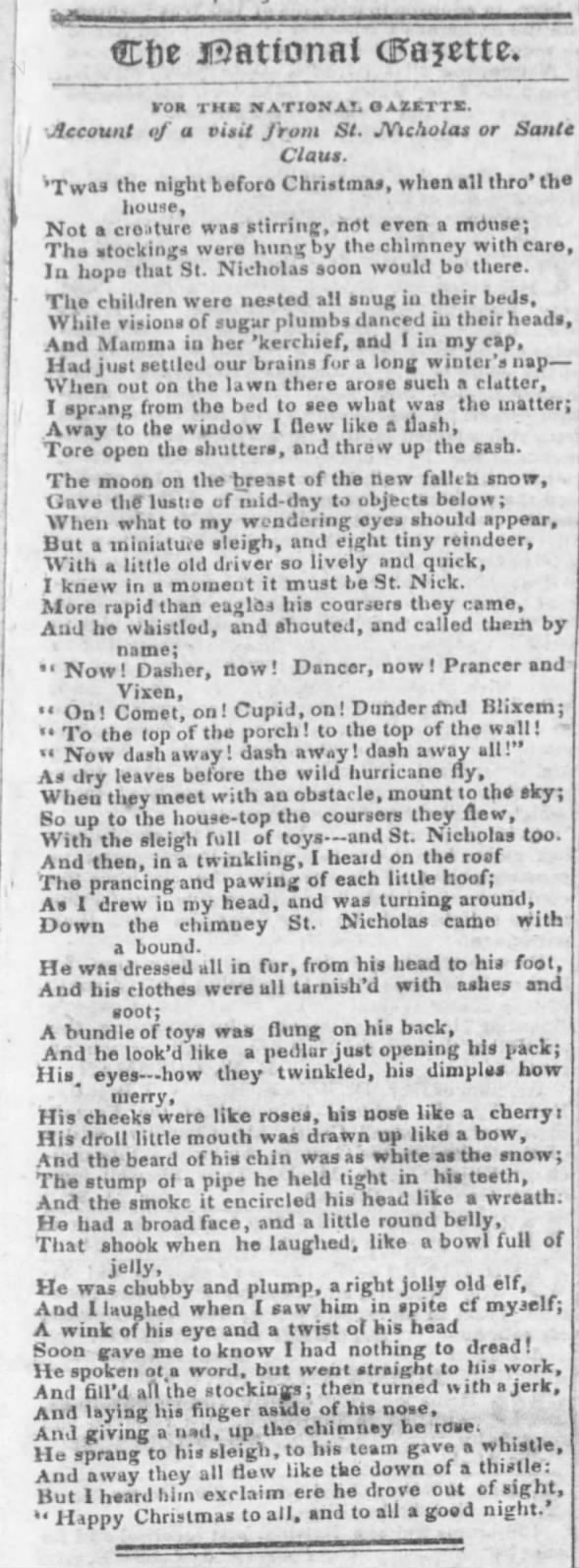

| Howitt's Journal of Literature and Popular Progress - January 1, 1848 |

In Germany, the servants of tradesmen come for New-Year's gifts, as they do for Christmas-boxes with us; and your baker sends you a large cake, like a couple of great serpents wreathed into two connected circles, perhaps originally intended to represent the old year and the new.

The Dutch, a kindred nation, carried over their national custom to America; but singular enough, one of the chief features of their New Year's-Eve is the arrival of Santa Claus, with gifts for the children, and whose figure as represented by an American artist, and which has been handed to us by an indefatigable American friend we present to our readers at the head of this article.Howitt's Journal gives Santa a good, practical excuse for not showing up in the U. S. until New Year's. He's been working hard all month and only made it to northern Europe a couple of weeks before Christmas:

Santa Claus is no other than the Pelz Nickel of Germany and the North; he is in fact, the good Saint Nicholas of Russia, the patron-saint of children; he arrives in Germany about a fortnight before Christmas, but as may be supposed from all the visits he has to pay there, and the length of his voyage, he does not arrive in America, until this eve. Here he is, sitting before the empty fire-place of an American house, with his foot on the old fashioned dog, a little after midnight, all the family having retired to bed to be out of his way, and having hung up the stockings that he may fill them with gifts. Here he sits, smoking his pipe, and delighting himself with the thought of what he shall leave for the children, and of the delight and surprise in the morning. --"New Year's Eve in Different Nations" in Howitt's Journal Volume 3

More testimony for the expected arrival of Santa Claus on New Year's night may be found in the "Address of the Carrier" on New Year's Day 1819, as published in the Weekly Visitor, and Ladies' Museum (January 9, 1819):

While young and old so gay and pleasantTo be clear, New Yorkers in the 19th century might expect Santa Claus at Christmas, or New Year's, or both. As a letter signed "Jeptha" in the New York American explained,

Exchange their New Year's wish and present;

While children round their parents press

With clamor,—anxious to possess

The Stocking, hoped with riches fraught;

Which good Old Santaclaus has brought;

Who yearly down the chimney comes

With Rods and Toys and Sugar-Plums,

And leaves for naughty girls and boys

The whips—but for the good, the toys—

--1819 Carrier's Address

"he sometimes comes on New-Year's night to dispose of the refuse of his Christmas luggage." --New-York American for the Country, January 3, 1824."A Visit from St. Nicholas" had only just appeared, anonymously, in the Troy Sentinel (December 23, 1823), so the 1824 description of Santa's physical appearance by "Jeptha" offers a nice, detailed view of what Santa looked like before the influence of Moore's "Visit." A similar conception may have influenced the artist Robert Weir, whose 1837 "Santa Claus, or St Nicholas" in part resembles the "little short hump-backed man" depicted in 1824 by "Jeptha":

"... this Saint Nicolas, for that is his proper name, he is the tutelary saint of this city, and chiefly favours the rising generation, to whom, on every Christmas eve, he brings various presents, adapted to the age or capacity of the receiver—he is a little short hump-backed man, with sharp grey eyes buried beneath ponderous black brows, which curve forward to join the sides of a long crooked hawk-bill nose, which overhangs a toothless trench beneath, that serves him for a mouth, though the beaked chin curves up so near the end of the nose, that it is difficult to conceive of any thing passing between without being impaled on the one or the other; his head is immensely large, and sets like a huge extinguisher upon his small body beneath, whose form is concealed by an immense wrapper coat filled with pockets, each stuffed to its limits with cake, almonds, raisins, toys, &c.; his feet are armed with a pair of skates, indicating that he comes from Holland, and, thus accoutred, he skates up and down the nursery chimnies, leaving his largesses behind him in every direction, and there's not a grown person but recollects with pleasure, nor a child but anticipates with delight, the well stuffed stocking of Santa Claus."

|

| Saint Nicholas 1837 by Robert Walter Weir via Wikimedia Commons |

Nothing could exceed the joy of the children on New Year's morning, when awakening with the first dawn of light, they jumped up eagerly to examine their stockings, which, certain of "Santa Claas" bounty, they had had suspended the evening before from the bed post--and which, according to their anticipations were full to overflowing." --quoted in The Battle for Christmas (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), page 163.As discussed in another post, one extant letter from Sophia Hawthorne to her daughter Una shows that even as late as 1852, children could rightfully expect presents from old St Nick on New Year's morning, after his annual visit on New Year's Eve.

"St Nicolas says he cannot put any of his presents into your funny long stocking, & so he asks me to write you a note & put it in, that you may not be disappointed; for he is a very kind old gentleman. So as it is the end of the old year, & in a few hours the new year will begin, I will say a few words of loving counsel...." --Sophia Hawthorne, letter to Una Hawthorne [1852] with a New Year's message from St. Nicholas. Accessible online courtesy of The New York Public Library Digital Collections.In any event, by New Year's Eve 1832 the various traditions about when Santa Claus comes were pretty well mixed up, even (or rather, especially!) in New York City. Christmas or New Year's? Wait, how about St. Nicholas' Day, December 6th? On New Year's Eve a Philadelphia newspaper reprinted this item, without comment, from the New York Courier:

|

| Poulson's American Daily Advertiser - December 31, 1832 via GenealogyBank |

SANTA CLAUS.—A correspondent inquires of us under this signature "whether Santa Claus, with his stocking is not confined in his pretended visits to the eve of the new year and of course his introduction on Christmas eve inappropriate." Santa Claus is Saint Nicholas and his visitations always take place in Holland on Saint Nicholas' day, which falls we believe on the 6th December. How the day came to be celebrated here either at Christmas or on New Year's day we are unable to say.—The last chapter in The Book of St Nicholas by James Kirke Paulding makes a fractured fairy tale out of "The Ride of Saint Nicholas on New Year's Eve."

In 1844, correspondent "L. P." of the Boston American Traveller described New Year's festivities in upstate New York. "L. P." especially loved the tradition of social visits as then still practiced in Waterford and urged Bostonians to adopt the "glorious" New York mode of celebrating the New Year:

"let us Yankees copy the glorious New Year's hospitality of the New Yorkers, in exchange for the compliment they have paid us in adopting our Thanksgiving."Waterford, New York still expected presents from "old Santa Claus that honest house-breaker" on New Year's day.

|

| Boston American Traveller - January 9, 1844 |

"A happy New Year! a happy New Year!" blessings on old Santa Claus that honest housebreaker, braying of penny trumpets and other boisterous mirth of the younger children (we are all children to-day) attests that the good Saint has not been remiss in his annual visits, now comes the display of stuffed stockings which have been duly hung up to receive the old fellow's favors and now you are fairly waked by the clamor, up you jump quickly for New Year's day dawns on no laggard, and you have the busiest day of your life before you." --"L. P." on New Year's Day in Waterford, New York; from the American Traveller [Boston, Massachusetts] January 9, 1844 via GenealogyBank.Under the heading "New Year's Day," the holiday editorial in the New York Truth-Teller (December 28, 1839) affirms among other things the persistent belief that Santa comes on New Year's night:

"The children will of course have their stockings in the chimney nook, to receive the innumerable bounties of the generous "Santa-Claus" or St. Nicholas, in loading whose huge panniers many a confectionary and toy shop will be stuffed."

On January 2, 1841 The New York Mirror published an illustration titled ST. NICHOLAS, ON HIS NEW-YEAR'S EVE EXCURSION (AS INGHAM SAW HIM,) IN THE ACT OF DESCENDING A CHIMNEY." Printer and bookseller Daniel Fanshaw wrote the prose essay (signed "D. F.") that was featured along with the front-page picture by "Ingham."

|

| New York Mirror - January 2, 1841 |

"... we prevailed upon our friend Ingham to gives us a sketch of him, just as he saw him one bright, frosty, moonlight night, as he was returning home late from a party of friends. As we had not time for a copper or steel plate engraving, we got our young friend Roberts to do his prettiest on wood, that our subscribers might have an opportunity of becoming familiar with the good-natured countenance of our old patron, who, in these degenerate days, is very seldom seen among us New-Yorkers; and we feel that our friend Ingham has been a very highly favoured mortal in being permitted to see him whom we have so many years longed to get a peep at. St. Nicholas knows how often we have hung up our stockings by the fire, and hied off to bed on New-Year Eve a full hour earlier than usual, lest he might pass our house because we were not yet asleep, and we find our stockings empty in the morning in consequence of our being night spooks. He knows how often we have anxiously and fearfully peeped up the chimney to see if he was not yet there; and yet he has never deigned to show himself to us, but has allowed friend Ingham to have a full and deliberate view....""Ingham" by the way is Charles Cromwell Ingham (1796-1863) the Irish-American painter and a founder of the National Academy of Design. On another page in the same issue of the New York Mirror (January 2, 1841), editor George Pope Morris reprinted C. C. Moore's "A Visit from St. Nicholas," altering the first and last lines to make St. Nicholas arrive on New Year's night.

'Twas the night before New-Year, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse....

Related post: